ICE Surveillance

ICE is collecting data on hundreds of millions of Americans and using sophisticated surveillance technologies to track them—both immigrants and US citizens.

Here’s how they’re doing it.

The surveillance technologies used by ICE are supplied by some of the most prolific brands in Silicon Valley—most notably Palantir. Other ICE contractors are more obscure surveillance companies shrouded in secrecy and offering highly sophisticated spyware, ripe for misuse and implicated in gross human and privacy rights violations perpetrated by authoritarian regimes across the globe.

Such opaque tools, with so little apparent oversight or public accountability, carry inherent potential for abuse and pose a significant threat to Americans’ privacy and civil liberties. These risks are amplified by the Trump administration’s flagrant disregard for civil rights and restrictions on federal law enforcement power amidst its cruel, haphazard campaign to apprehend and deport immigrants living in the United States.

Millions of innocent Americans—immigrants and citizens—are unknowingly caught in the middle of it, their privacy invaded and their safety at the whim of an increasingly imperious agency.

These are some of the companies working with ICE to maximize its surveillance and intelligence capacity:

Palantir has been providing US intelligence with data analysis tools for 20 years starting with the CIA in 2005. Since then, Palantir has worked with DHS on several occasions.

ImmigrationOS

ImmigrationOS is the most recent software developed by Palantir for ICE. In April 2025, ICE paid Palantir $30 million to build a tool that will allow the agency to more efficiently manage its enforcement and removal operations. ImmigrationOS will use AI to sift through immigration records and a massive databases of Americans’ personal infromation to identify immigrant individuals as optimal targets of enforcement actions and deportation. ICE will also be able to track immigrant self-deportations with “near real-time visibility”. It is not clear what data ImmigrationOS will use, but ICE already collects data from a number of federal, state, and local government agencies. The tool is supposed to be delivered to ICE in September 2025.

FALCON

FALCON is a data analysis and storage tool developed for ICE by Palantir since 2011 as a modified version of Palantir’s commercially available Gotham software. FALCON allows agents to search, analyze, and visualize ICE data and identify trends and generate leads used to investigate money laundering, smuggling, and import-export crimes.

Investigative Case Management (ICM) system

The Investigative Case Management (ICM) system is software developed by Palantir for ICE and used by its Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) division to compile and manage data, build case files, and transfer records internally and between government agencies or other external parties.

ShadowDragon is an open source intelligence (OSINT) company providing law enforcement with tools to analyze individuals’ online behavior and map their social networks.

SocialNet

SocialNet aggregates user data scraped from websites and social media platforms and assists law enforcement investigations. This tool helps ICE construct profiles of its targets and map their social networks by uncovering aliases, contact infromation, social media activity, and location data.

PenLink is a US-based company providing law enforcement and intelligence organizations around the world with data collection and analysis tools intended to streamline their investigations and assist them in identifying potential targets. Its PLX tool can intercept telephone calls and texts in real time and may access communications from social media and popular messaging services like Gmail, Facebook, and Discord.

Tangles

In September 2025, ICE paid PenLink $2 million for access to its Tangles software, which scours the open Internet and dark web to identify people of interest and construct comprehensive profiles of targets detailing their personal data, social media activity, contacts, location, movements, and behavior. It also includes a facial recognition search tool that can match a target’s image with other pictures of them in the Tangles database.

Babel Street provides data collection and OSINT products to governments and law enforcement. Their premier product, Babel X, allows clients to uncover the identities and sensitive information of targets with user data provided by websites and social media platforms, simply by searching their username, phone number, email, driver’s license number, or Social Security number. For example, if ICE wants to find out who owns a certain Instagram account, it can use Babel X to match the account with real names, emails, phone numbers, and other personal information.

Here are the documents obtained by EPIC from ICE regarding its contract with Babel Street.

Locate X

Every mobile device is assigned an advertising ID used to track their individual users’ behavior behavior and generate data that is sold to marketers for targeted advertising. The user data associated an advertising ID includes device location. Babel Street purchases user data and maps the precise location and movements of mobile devices. It sells these maps to law enforcement as a product called Locate X. ICE uses Locate X to identify mobile devices and their owners, find their location, and track their movements as they travel from home to work, to church, to school, or anywhere else they visit.

Paragon is an Israeli intelligence company, most famous for its flagship spyware product called Graphite. Its founders include former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and a former commander of the IDF’s Unit 8200, Ehud Schneorson. Paragon signed a $2 million dollar contract with ICE in late 2024 to provide its services for two-years, however its deployment was paused awaiting review of its compliance with an executive order limiting federal use of spyware purchased from foreign businesses. The hold was lifted in September 2025 and Paragon’s products are now available to ICE. Paragon has previously worked with US federal law enforcement, providing Graphite to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) in 2022.

Graphite

Graphite is a so-called “zero-click” spyware, meaning it can be installed on a target’s device without any interaction from them at all. They don’t have to click a link or download a file—often just receiving a message is enough for this kind of spyware to be deployed. Graphite allows its customers to break into their target’s mobile device and access all of its data, including messages, photos, location services, and even encrypted data like WhatsApp messages. It can also activate the device’s microphone and effectively turn it into a listening device.

In 2024, an investigation by the Citizen Lab discovered that Graphite was used to target several Italian journalists and activists. The Italian government denies it spied on them, though Paragon quickly cut ties with its Italian customers after details of the investigation became public in February 2025. Similar spyware tools from Paragon’s competitors, particularly NSO Group, are implicated in several high profile cases of mass surveillance, violence, and human rights abuses against journalists, activists, and civil society by authoritarian regimes around the world.

Where does ICE get its data from?

Law enforcement

State and local law enforcement agencies frequently share criminal justice information with ICE through formal databases, informal communication, and designated data-sharing programs. This information allows ICE to identify, locate, and detain non-citizens who come into contact with the criminal justice system, even for minor offenses. Key data points include fingerprints, arrest and booking records, outstanding warrants, probation or parole status, and release dates from local jails. Some local law enforcement agencies even notify ICE when it detains an individual who they suspect to be undocumented or wanted for removal.

Gang databases

ICE relies heavily on gang databases compiled by state and local law enforcement across the country to identify individual immigrants for arrest or deportation. These databases are shared directly with ICE by the police departments that operate them, or indirectly as their contents are passed between agencies along a convoluted network of criminal justice information pipelines and partnerships. Even gang databases maintained by police departments in sanctuary states and municipalities are routinely accessed by ICE despite the best efforts of local officials to restrict data sharing with federal immigration enforcement.

Gang databases are notoriously inaccurate. The criteria for an individual to be included on one are often dangerously trivial, and frequently erroneous allegations of gang membership are based on vague associations and circumstantial evidence. These databases are not publicly searchable, audits of them are rare, and oversight is virtually non-existent. What is certain: false allegations of gang affiliation destroy the lives of innocent people navigating the immigration justice system. A flimsy or unfounded accusation of gang membership made against an immigrant is enough to sink their asylum application, disqualify them for DACA status, and even land them in a foreign prison.

Federal agencies

A number of federal agencies and programs outside of law enforcement share their records with ICE or operate databases accessible to ICE. These include:

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

US Department of Veteran’s Affairs

Supplemental Nutritional Aid Program (SNAP)

Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

Social Security Administration (SSA)

US Department of Education

US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

US Postal Service (USPS)

DMVs

ICE has an extensive history of working with state departments of motor vehicles (DMVs) to obtain records and perform searches of driver’s license photos using facial recognition technology. There is no formal procedure for information sharing between state DMVs and DHS, though there are a few methods ICE uses reliably.

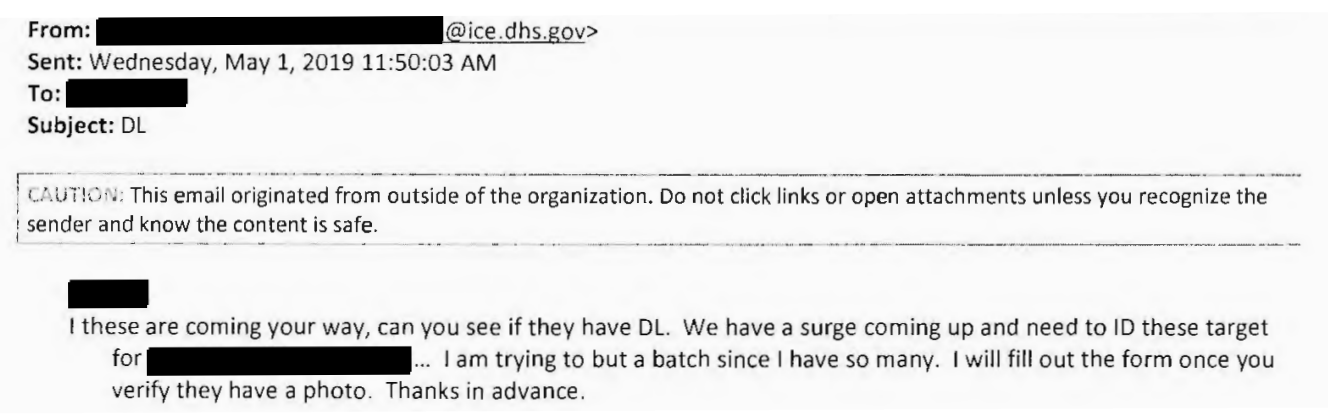

First, ICE may contact state DMVs directly to request records and information. This process isn’t always as formal or transparent as you might expect. ICE agents frequently email casual requests for information to individual DMV employees.

Two emails from ICE agents to Georgia DMV employees requesting facial recognition searches, obtained by the Center on Privacy & Technology through FOIA request.

For over 20 years, ICE has maintained formal data-sharing agreements with state DMVs, providing ICE with direct access to state DMV databases and free rein to perform search queries and match pictures with driver’s license photos using facial recognition software. Through these agreements, ICE has access to the driver’s license photos of 1 in 3 American adults.

Several states have since passed legislation prohibiting their motor vehicle departments from sharing sensitive data, like drivers’ personal information or driver’s license photos, with federal law enforcement. However, restrictions on DMV data sharing have hardly curtailed ICE’s data access. Forty states share DMV records with the International Public Safety and Justice Network, or Nlets—a service used by the federal, state, and local governments in all 50 states to share and collect agency data for law enforcement use, all in one place. ICE also has access to Nlets and, by extension, the DMV records associated with around 194 million drivers.

When ICE can’t access DMV records through those routes, it purchases them from private data brokers. Twelve states have sold the DMV driver’s license records of almost 90 million drivers to just LexisNexis Risk Solutions alone.

ALPRs

State and local governments across the United States use automated license plate readers (ALPRs) to capture images of license plates and track vehicles for toll collection and law enforcement purposes. Thousands of ALPR systems are operated by surveillance technology and forensic intelligence companies like Flock Safety and Vigilant Solutions under contracts from local governments and law enforcement agencies nationwide. These companies offer access to software which analyzes ALPR recordings using artificial intelligence and machine learning programs, identify vehicles, log captures in searchable databases, cross-reference their analyses with police databases and watchlists, and alert law enforcement of potential stolen and missing vehicles or persons of interest. DHS previously proposed to create a federal database of complied ALPR data from across the country, but scrapped the plan after receiving backlash from privacy rights advocates.

20 billion license plate scans per month

5,000+ communities in the Flock network

4,800+ partnered law enforcement agencies

49 states served by Flock

Law enforcement agencies with access to there private databases can search for license plate data recorded anywhere in the country within the ALPR network. Searches of the Flock database are logged, and police must provide a reason for their query. Some states restrict sharing of ALPR data with federal law enforcement, especially data that can be used in immigration enforcement operations. Reporting from 404 Media in May 2025 revealed that police departments across the country were performing searches of the Flock database on behalf of ICE, leaving explanations for their queries like “immigration”, “ice”, “dhs”, or “homeland” in the logs. In August 2025, an audit by the Illinois Secretary of State alleged that Flock provided DHS with access to its database and allowed federal immigration enforcement to view ALPR data captured in Illinois, violating state law.

Data brokers

To fill the gaps in its data with records that can’t be obtained from government or public sources, ICE purchases massive quantities of data worth billions of dollars from major data brokerage firms. While ICE generally does not disclose the specific kinds of data it purchases from brokers, documents uncovered through FOIA requests and leaks indicate that ICE receives information including personal data, vital records, property records, utility records, financial data, credit reports, telecommunications and mobile location data, Internet and social media user data, criminal justice data, real-time incarceration and release information, DMV records, ALPR data, and much more.

LexisNexis collects a truly colossal amount of data from a wide array of public and proprietary sources—it sorts through billions of datapoints to construct unique identities for 276 million Americans. LexisNexis currently has a $22.1 million contract to provide ICE with data and data analysis services until 2028. The kinds of information ICE receives from LexisNexis include:

Real-time booking records from jails and prisons

State DMV records

Utility records

Social media/Internet user data

Property records

Vital records

Appriss, a subsidiary of Equifax, collects incarceration data from over 2,800 correctional facilities across the United States and provides real-time access to booking and release records, updated every 15-minutes, through its Justice Intelligence service. ICE uses Justice Intelligence to find immigrants held in jails and prisons.

Venntel collects cell phone location data for over 250 million mobile devices in the US and sells it to law enforcement. ICE uses that data to identify immigrants and the people they interact with, track their movements, and monitor the behavior of entire communities. Venntel received $330,000 in contracts with ICE between 2018 and 2022.

The Airline Reporting Corporation is a data brokerage company owned and operated by nine major passenger airlines which settles ticket transactions between airlines, accredits US travel agents, and provides industry data analysis. Reporting from WIRED and 404 Media revealed that the ARC entered an agreement with Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) in June 2024 to provide the agency with domestic flight records containing their passengers’ names, itineraries, and payment information.