Tracking ICE operations and US immigration policy.

See ICE? Here’s what to do.

Follow these steps if you see ICE in public.

1. Identify

2. Record

3. Inform detainees of their rights

4. Ask detainees if they would like you to contact someone

5. Ask agents where they are taking detainees

6. Alert your network and community. Call rapid response.

How to identify ICE:

Learn to recognize ICE agents, their vehicles, and the deceptive tactics they use.

URGENT

⋅

ACT NOW

⋅

URGENT ⋅ ACT NOW ⋅

ICE now has access to the health records and personal data of 80 million Medicaid patients.

Protect your privacy. Tell your elected representatives that you don’t want ICE to view your personal information and sensitive health data.

URGENT

⋅

ACT NOW

⋅

URGENT ⋅ ACT NOW ⋅

Who are “the worst of the worst”?

210,000

arrests made by ICE since January 2025

58,000

people in ICE detention

71%

of ICE detainees DO NOT have criminal records

Immigrants are far less likely to commit crimes than US-born citizens.

Since 1980, the share of the US population who are immigrants has more than doubled.

1980: 6.2%

2022: 13.9%

In that same time, the US average crime rate fell 60.4%.

1980: 5,900 crimes per 100,000 people

2022: 2,335 crimes per 100,000 people

According to a 2020 federal study of Texas crime data, legal immigrants committed 25% fewer crimes than US-born citizens and undocumented immigrants committed about 65% fewer crimes than US-born citizens.

More immigration does not lead to more crime. It never has.

Here’s who has been rounded up:

-

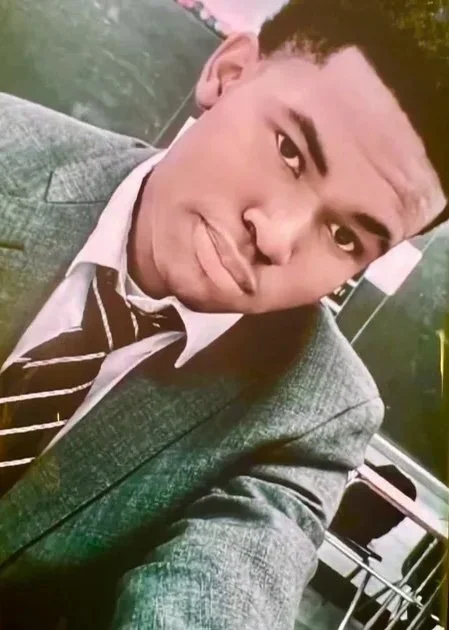

Andry José Hernández Romero

AGE 32, VENEZUELA

Romero is a gay makeup artist from Capacho Nuevo, Venezuela who was initially detained at the San Ysidro border crossing in August 2024 after entering the United States to seek asylum. He remained in CPB detention for seven months before he was unlawfully rendered to CECOT, a notoriously hellish El Salvadoran prison, along with hundreds of other Venezuelan nationals by the Trump administration in March 2025. After four months in CECOT, Romero and the remaining Venezuelan detainees were released and returned to Venezuela. Romero says he was beaten, tortured, and sexually abused by CECOT guards.

-

Jose Hermosillo

AGE 19, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

Hernandez is a 19-year-old US citizen from Albuquerque, New Mexico who was detained by CPB in Nogales, Arizona. He got lost after visiting Tuscon and approached Border Patrol officers for help. The officers arrested Hermosillo, claiming that he lacked “the proper immigration documents”, and he was held at an ICE detention center for 10 days without explanation.

-

Juan Carlos Lopez-Gomez

AGE 20, GEORGIA, UNITED STATES

Lopez-Gomez was a passenger in a car that was pulled over by Florida Highway Patrol for speeding. He was arrested and jailed for 48-hours after being misidentified as the subject of an ICE detainer despite being a US citizen who was born in Georgia.

-

Marcelo Gomes da Silva

AGE 18, BRAZIL

Gomes da Silva is a Massachusetts high-school student who immigrated to the United States from Brazil with his family at the age of 7. He was arrested by ICE in late April 2025 while driving to his team’s volleyball practice. ICE said that Gomes da Silva was not the intended target of their arrest, but was detained nonetheless because he illegally entered the United States as a child. His arrest outraged his local community—students from his high school staged a walkout in protest of his detention—and he was released after six days in ICE custody.

-

Matilde Rivera

AGE 54, MEXICO

Rivera is a Mexican woman who has lived in the United States for the last 29 years. She was selling tamales from a stand in the parking lot of a Lowe's in Pacoima, California when she was arrested by ICE on June 19th. ICE agents were sweeping the area when they approached Rivera’s stand in a white, unmarked car with tinted windows. The agents lunged from the vehicle and rushed to detain her. She did not attempt to flee. Rivera says the agents did not identify themselves as ICE personnel or law enforcement officers, nor did they present her with an arrest warrant. An ICE agent grabbed her from behind while another scrambled to handcuff her. She fell to the ground, screaming that she could not breathe and complaining of chest pain. Rivera was taken to a nearby hospital where doctors discovered that she had suffered a minor heart attack during the encounter.

-

Alan Pierre

AGE 20, HAITI

Pierre is a high school student from Spring Valley, New York and a Haitian man who immigrated to the United States as a refugee with Temporary Protected Status (TPS). He was apprehended by masked ICE agents on June 4th in Lower Manhattan after leaving a routine immigration hearing. He had a green card application was pending at the time of hiss arrest. Pierre was held in ICE detention for five weeks, causing him to miss his final exams and the deadline to sign up for summer school. The Trump administration’s Department of Homeland Security intends to end the TPS program for Haitian migrants in September 2025.

-

Sara Lizeth Lopez Garcia

AGE 20, COLOMBIA

Garcia is a resident of Mastic, New York and student at Suffolk County Community College studying to become an interior designer. She even designed a part of a local women’s shelter. Garcia and her mother, both immigrants from Colombia, were arrested by ICE at their Long Island home on. Garcia was just a month away from getting married to her fiancé and was in the process of obtaining permenant residency in the United States. She remains in ICE custody at a detention center in Louisiana and awaits a hearing and probable deportation.

-

Kasper Eriksen

AGE 32, DENMARK

Eriksen lives with his wife and four children in rural Mississippi, where he works as a welder. He is an immigrant from Denmark who moved to the United States in 2009, became a legal permanent resident, and had been pursuing citizenship for several years. In April 2025, at his last meeting with immigration officials to finalize his naturalization, Eriksen was arrested by ICE agents and transported to Louisiana detention center. The reason for his detention: he had forgotten to fill out a single immigration form, Form I-175, back in 2015 while beginning the naturalization process. Immigration authorities could unsuccessfully attempted to notify Eriksen of his error and they promptly ordered him to be removed. For the next ten years, he attended the required meetings with immigration agents and followed all the necessary steps to obtain citizenship. He is currently detained and faces deportation.

-

Joel Gutierrez

AGE 48, MEXICO

Gutierrez is a 48-year-old construction worker from the Phoenix metropolitan area who was arrested by ICE on the morning of June 4th while driving to a worksite. He and his wife moved to the United States from Mexico in 2000 and has lived in Arizona since. They have four children, two of whom were born in the United States and are citizens; their youngest child is 9-years-old. Gutierrez is undocumented, though he had previously applied for citizenship immigration status without success. He is being held at an Arizona ICE detention facility.

Conditions in ICE detention are abhorrent.

It’s not by mistake.

Cruelty is the point.

ICE Surveillance

ICE is collecting data on hundreds of millions of Americans and using sophisticated surveillance technologies to track them—both immigrants and US citizens.

Here’s how they’re doing it.

Longstanding agency policy discouraged ICE from carrying out enforcement operations at sensitive locations—like churches, schools, and hospitals—deemed off-limits given the privacy and ethical concerns associated with them. Directives restricting ICE activity at sensitive locations were immediately rescinded by the second Trump administration, suddenly expanding ICE jurisdiction and redefining its relationship with civil rights.

Can ICE enter places of worship?

ICE cannot conduct enforcement activities in a place of worship without an administrative or judicial warrant authorizing them to do so.

Can ICE enter healthcare facilities?

ICE is permitted to enter and freely search any publicly accessible space within a healthcare facility. Restricted and private areas, like examination rooms are off-limits without a judicial arrest or search warrant. Healthcare providers cannot be compelled to disclose a patient’s immigration status or any other personal information.

Can ICE enter schools?

ICE may enter schools, however, they are not entitled to access areas closed to the general public, such as classrooms, without a judicial warrant. School staff are not obligated to disclose students' personal information, nor must they allow law enforcement contact with students absent a court order. ICE can still operate at bus stops, in parking lots, on sidewalks and streets, or any other public space on or near school property.

Can ICE enter shelters?

ICE can enter any part of a shelter that is open to the public. They might need a judicial warrant to enter areas which the shelter has designated as “private” or “non-public”, like sleeping quarters and offices.

ICE in immigration court

How does ICE maximize deportations and keep up the White House’s daily quota of 3,000 arrests if its targets are legally entitled to have their cases heard in immigration court? With a crooked and predatory tactic: arrest immigrants at their immigration hearings.

Immigrants who have lived in the United States for fewer than two years without legal status can be deported without an immigration hearing or any opportunity to fight their deportation in a process called "expedited removal”. However, anyone with a pending immigration case, regardless of their immigration status or the amount of time they have spent in the United States, has a due process right to receive a hearing and cannot be removed until their proceedings have concluded in immigration court. This is especially important for asylum seekers who enter the United States to request humanitarian immigration relief and may remain in the country while their asylum application is being processed.

ICE identifies recent immigrants with cases pending in immigration court. Their agents gather at courthouses and in the halls of immigration courts across the country and wait for those immigrants to appear for their hearings. When a target arrives, ICE quickly petitions the presiding immigration judge to dismiss their case. The judges, employees from the Justice Department, frequently yield to ICE's requests and toss out immigrants’ cases, denying them even the chance to argue for their right to stay. There is no hearing. No verdict. With their cases dismissed, asylum seekers and other immigrants fighting for status lose their legal protections from deportation - fair game for expedited removal. They’re promptly handcuffed by anonymous ICE agents, prodded into idling vans, and disappeared to notoriously overcrowded and remote detention centers.